The Only Tourist in Havana, December 2021

Student artwork at ISA (Instituto Superior de Arte) Havana. Photo: Karen Dubinsky

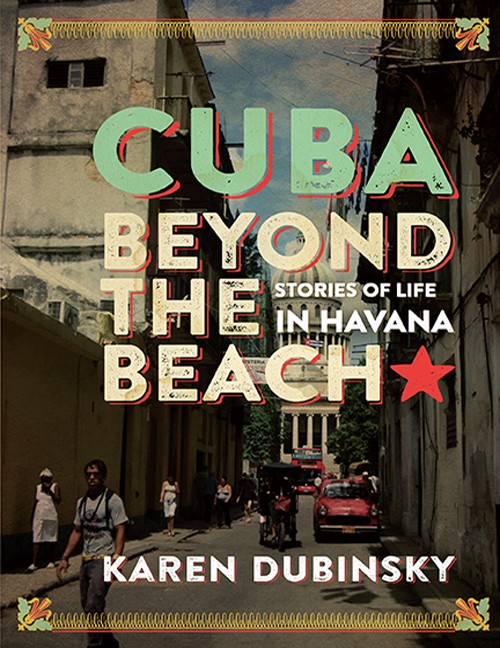

In 2016 I wrote a book about Havana, Cuba Beyond the Beach: Stories of Life in Havana. It offered a neighbourhood-eye view of the lives of friends and colleagues I’ve worked with in my capacity as a professor who has brought Canadian students to study in Havana for over a decade. I have been visiting Cuba since 1978, when, as a starry eyed twenty-one-year-old, I attended the World Festival of Youth and Students which celebrated “Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship.” Cuba and I have both changed some since then, but still my book ended on a hopeful note. I finished it just as Barack Obama and Raúl Castro were making overtures towards “normalization” and a spirit of hopefulness was palpable in Cuba, especially in the cultural world. Two US presidents, a global pandemic and an uncommon series of public protests later, I returned. What did I find in my corner of Havana today?

Who did I find ought to be the first question. I would need at least two hands to count the friends, children of friends or acquaintances who have left the country. Some for education in Canada, Europe or Brazil, others for jobs in the US. During the pandemic, many with resources have left for refuge or at least temporary breathing space with family in other parts of the world. Two beloved colleagues, both University of Havana professors, died.

After a series of pandemic-mandated closings, airports have reopened and visitors are arriving, principally to the beach resorts. Less so, at this point, to the city. As I wandered Havana, Leonard Cohen’s ironic poem The Only Tourist in Havana, penned during his visit in 1961, resonated. The city is darker and quieter than it used to be. Everyone wears masks, everywhere, including outside. Curfews have been lifted, schools at all levels have reopened, along with some museums and galleries. Some favourite cafes and restaurants did not survive, as in Canada others successfully made the transition to takeout or home delivery and have now reopened. Some of the large hotels remain closed.

Even this level of “normalcy” in an economy dependent on tourism is only possible because of extremely high vaccination rates, which the country achieved by producing its own vaccine – actually multiple vaccines. Every single person I spoke to in Havana knew people who had contracted COVID or had themselves. After a disastrous spike in COVID rates this summer as the Delta variant made its way through the world, Cuba has one of the highest vaccination rates globally, in the 80% range, (including children). Nothing is certain, but in terms of COVID, it seems as though a corner has been turned.

But at a tremendous cost. Food scarcities are everywhere, and prices are impossible, at least three times higher in the food sector. A series of disastrous monetary reform measures undertaken mid pandemic attempted to unify the former two currency system, but it has just exacerbated racialized economic inequalities. Cubans with hard currency can shop at one store, which contains little, all at huge prices. Those with only Cuban currency shop at another, which also contains little, at huge prices. Every store has what seems to be a constant lineup. Neighbours and friends alert each other when valued products arrive; one friend showed us her food supply telephone tree which contained a dozen names. Others use social media like WhatsApp for the same purpose. Once alerted, people organize their waiting time together. For big ticket items like chicken, people expect to spend five or six hours in line. “It’s like a picnic, without food,” a friend explained to me, half ironically.

These scarcities include household goods and, ominously, medicines as well. That a small country in the Global South, economically blockaded by the US, came up with its own vaccine is remarkable. The current scarcity of almost all medical supplies – from simple aspirin to antibiotics to cancer related drugs – is a nightmare. Over the past year there have been concerted campaigns of medical donations from groups around the world with political affinities for Cuba, as well as smaller groups of friends and family members organizing people-to-people shipments. Authorities lifted importation restrictions (for food and medicine) for travellers as well, and Cubans are encouraged, through a recent campaign of TV ads, to have visitors bring them food and other supplies. This “temporary” measure was just extended another six months, to July 2022. I read about this extension the day after I returned to Canada, and my initial impulse was “good, maybe I could organize another trip with bulging suitcases.” Two seconds later a Cuban friend in Canada gave me a needed reality check; this is also a tremendous sign of desperation. The suitcase solution to food insecurity understandably alarms Cubans in the diaspora; it is hardly a sustainable step towards economic reform. Cuban economist Juan Triana Cordoví recently asked a pertinent question: why has it been easier for the country to produce a sophisticated vaccine than to keep pork or chicken on the table?

These are a few of the many pressures that lead to a series of protests in Cuba over the past year. “Unprecedented” is a word that has been overused to describe these events, but it fits. In November 2020, artists and other cultural figures gathered in the hundreds outside the Ministry of Culture, protesting worsening limitations on freedom of expression. People connected to the San Isidro movement in an Old Havana neighbourhood drew attention to these and other restrictions with hunger strikes. Finally, there were the explosive protests of July 11, 2021, when people all over the country took to the streets.

I did a great deal of listening when I was in Havana. In my circle of friends and acquaintances I heard a range of opinions and grievances as well as a great deal of pain. Some started their story of the Cuban crisis in the US: Trump tightened the blockade and other restrictions, and Biden has, despite promises, done nothing to change it. Friends who work in tourism began their explanations with the devastating effect of COVID on international travel. Some have lost what little faith they had in their own government. “Socialism is just a bad economic system; it’s not working in Cuba any more than it has anywhere else,” Eduardo told me, more directly than he has in the past. Many are furious with the Cuban government’s decision to make monetary reform a priority during the global pandemic, which exacerbated already huge disparities between hard currency holders (those with family outside the country, mostly white Cubans) and peso-earners, among whom Afro Cubans predominate. A friend who is set to retire from his job in a state agency pulled out his employment file, and, choking back tears, showed me thirty plus years of citations and commendations for exceptional service. He’s going to retire on a monthly pension which would, at the current official exchange rate, barely buy a single meal in an economically priced restaurant. Another friend teared up as she told me of her daughter’s imminent departure, to join her husband in the US. “It’s a business” she said, referring to the migration system. “The government wants young people to leave so they can send money back to us.”

When I asked people what they believed might make change, the answers were also all over the map. “People are living inside their own problems they have no space to think beyond that,” Jorge told me, which seemed an accurate statement. People had mixed views about the July protests. One greeted me jokingly with a “Patria y Vida” (the title of a song that has become the slogan of the civic opposition movement), then pretended to look around to see if he was overheard. Another had been so angry at me for something I wrote with a colleague in July, lamenting the Cuban government’s hard-line response to the protests, she sent me a rare email telling me how wrong I was. Five months later, she is no less convinced of her pro-government position, but she thanked me sincerely for coming back to visit even though times are so bad. One friend, a long-time party militant, declared that the protests were a wake-up call the government should have heeded before. Others decried what they believed was the use of violence by protestors and lamented that the leadership of the opposition movements was “clownish” and lacking in respectability. “No one is going to bring this government down like that,” one declared (in a tone that evaded the question of whether that should happen or not). Leila told me about a text she received from a Cuban friend in Miami the day of the protests, urging her to hit the streets. “I was so angry at her it took me two weeks to respond,” she told me. “How dare she. Sitting in the comfort of Miami!”

Among the people I spoke to, certainly scarcities of food and medicine and loss of purchasing power were top of mind. “Only the intellectuals and artists really care much about censorship and freedom of expression,” an academic colleague – who actually cares deeply – told me, though of course they are not unconnected. A photographer friend lamented that she hasn’t been able to take photos for months, since the protests, because authorities in her impoverished neighbourhood confiscate cameras from people to prevent the circulation of images of food lineups.

My academic colleague was extremely frustrated by the response of leftists outside Cuba. “Why can’t people outside Cuba see that you can be a leftist and at the same time be critical of this government?” he asked, echoing the words of Cuban historian Rafael Rojas, who termed this “reverse colonialism.” For Rojas, Cuban civic unrest is seen (by Cuban authorities and some leftists outside the country) as “ventriloquists of the empire.” “The Cuban reality is overdetermined by the dispute with the United States,” he writes, “Cuba, therefore, remains a colony.”

I left these conversations sadder and wiser, and more convinced than ever that, despite attempts to paint criticism as always and forever inspired by the US government, this is a conversation among Cubans. Which will require Cuban solutions. Of course, the US has intervened in Cuban affairs repeatedly since the 1959 Revolution. But when speaking to me about their reactions to the protests, not a single person told me they thought those who took to the street did so because the US government told them to. That argument, advanced repeatedly in Cuban state media, just didn’t come up. They were too busy being smart, informed, ironic, sad, frustrated, funny, and angry about their own country.

I spent an informative morning visiting the Martin Luther King Centre, a respected NGO that has been working in Havana since the 1980s. It is connected to the Baptist church and operates as a community education and resource centre in Poglotti, a well-known poor neighbourhood. During the pandemic they joined other NGOs, artists and community groups collecting material aid, mainly medical supplies, and distributing them to the various hotspots on the island. This kind of work outside the state system is relatively new; Cuba has had a complicated and contested relationship with NGOs inside and outside the country. But the work of the MLK Centre is hardly bourgeoise charity. I worked with some Cuban and Canadian friends this summer organizing funds and shipping many boxes of medical supplies from Toronto to Havana, so I was curious to see what they do. Kirenia Criado, a Quaker pastor who was on the receiving end of all those boxes, showed us how deeply embedded in their community domestic civil society groups can be. Her social justice activist spirit would be recognizable to anyone who works in these worlds, in any country. She spoke movingly about how the pandemic forced them to temporarily transfer their work from community building to simple survival. Hence the boxes.

Of course, there is nothing new about Cuban resilience and ingenuity. “Resolver” and “inventar” have been the language of survival in Cuba for decades. My partner and travelling companion Susan Belyea, who wrote a dissertation on Cuban food security, visited friends in Alamar, a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Havana, who in the last year cleared an impressive quarter acre lot near their apartment building and created a bountiful vegetable garden. She noted during this visit that gardens are more obviously visible in the city as well. The crisis has also created some impressive and useful opportunities for entrepreneurship. We dined on buffalo stew one night, thanks to the largess of a Canadian friend who had ordered it through an online grocery delivery site – one of many that have emerged during the crisis, for a mutual friend in Havana, who shared it with us.

What has always inspired me most in Havana – in addition to the people – is the arts, and especially the community of contemporary alternative musicians. In jazz, hip hop and trova there is a world of political debate, sometimes cloaked in metaphor, sometimes plain to see, always a sign of an active and vibrant conversation between musicians and their audience. My most recent visit coincided with the return to the stage of Interactivo, a jazz fusion band that just celebrated their twentieth anniversary. Entering “El Brecht,” the basement club tucked under the Bertolt Brecht Theatre where I have enjoyed a decade of amazing musical events, was the strangest and most normal thing I have done in the past two years. Even though musicians haven’t been performing in Cuba any more than they have been anywhere else in the world, they haven’t been sitting still either. Interactivo opened with a new song written by their leader, Roberto Carcassés, “Pero” (But). It was written on the occasion of the first large protest, November 27, 2020, at the Ministry of Culture, which brought people in the cultural world together to oppose limits (increasing in severity) on free expression. Hundreds of people had the audacity to show up, without permission, outside a government building. Carcassés would likely reject this song as representative of anything but his own view, which is the point. But his view, like those of so many I encountered in Havana, ought to be heard.

But

By Roberto Carcassés, November 2020

My translation

I have an aunt who is a Fidelista

I have an uncle who is a Trumpista

But I love both of them with all my heart

I have all kinds of problems,

Material and intellectual

In the lineup for chicken just as with the Ministry

I’m a revolutionary

Also, I’m not

They’re both just points on a watch

I’m a free Cuban

I always show up

I’m not CIA nor G2*

I’ve seen Fernando** in my concerts

Also Luis and Carlos Manuel***

They all enjoyed themselves very much at Bertolt Brecht

Sometimes words confuse everything

But I’ll tell you one thing

There’s nothing that can’t be resolved by music and marijuana

I could be wrong

It’s just my opinion

Representing a minority of one

Association by affinity

It’s the best option

With freedom of expression

With love and responsibility

We’re all the same

Cubanidad

I’m a free Cuban

As Marti longed for

I’m Cuban

Ay, look at that woman

She’s the one I like

You like pachanga

You like the party,

I like my Cuba enjoying itself

I like my people dancing

With peace, love and prosperity we’ll keep going

Always forward, in front, struggling

But I love both my aunt and uncle with all my heart.

*Cuban state security forces

** Fernando Rojas, Vice Minister of Culture

*** Luis Manuel Otero, imprisoned artist, and Carlos Manuel Álvarez, exiled journalist

No comments:

Post a Comment