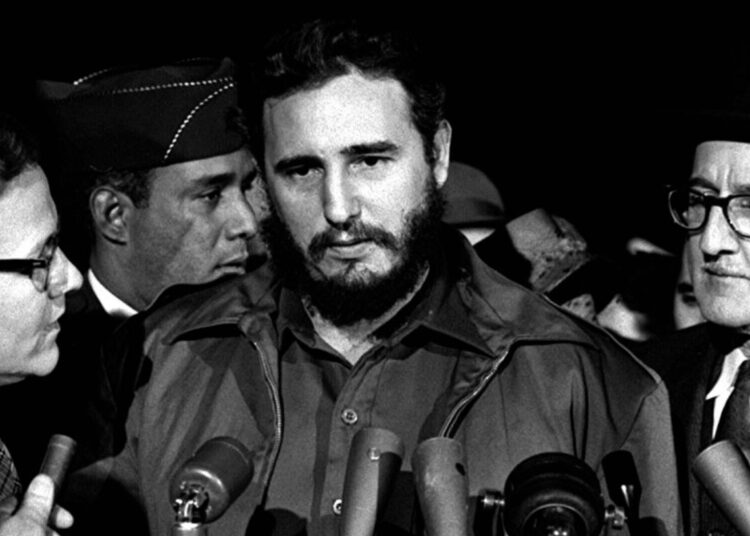

In a jungle of prejudices: Fidel and the Americans

The Revolution has triumphed 109 days ago, and he has been in the United States for five, where he has arrived as a guest of the Newspaper Publishers Association.

It is difficult for me to speak here in the middle of a forest of prejudices. I can speak here about a real revolution that is taking place near your country. Our revolution was made without hate of class. There was never a division from one class to another. Our revolution is a revolution for social justice, for the poor people, and of course, too, for the middle class. 1

This is Fidel Castro, 65 years ago, speaking in English to students at Princeton University. The Revolution has triumphed for 109 days, and he has been in the United States for five, where he has arrived as a guest of the Newspaper Publishers Association. Although on a “private” visit, he has spoken repeatedly in front of the big press, on high- rated television programs, and has even met with the Secretary of State, with senators and representatives of the foreign committees of Congress, and with Vice President Nixon himself. The photo of him waving to the crowd in Washington is on the front page everywhere. He is not yet 33 years old.

Before leaving Havana, Ambassador Bonsal made all kinds of recommendations on how to make the most of the trip. The diplomat, for whom Cuban politics is a crossword puzzle, believes that the trip will be the return trip, and it annoys him that the journalists have taken the lead over the Eisenhower Administration. He knows, by the way, that the general president was reluctant to invite him, waiting for Fidel and Cuba to enter through the ring. Instead, the guerrillas have slipped through the half-open door of the press, since closing it would have been a hassle (Eisenhower discreetly asked if they couldn't "deny him a visa").

The plan is dizzying, of course, like everything back then, but not so improvised. The Government's economic team, made up of top professionals, has prepared to talk with its counterparts from the North. The National Bank has sent a memo to the other side proposing an agenda on cooperation and financial assistance. And Minrex (the chancellor is not yet Roa, who served as ambassador to the OAS) has even hired a well-known American public relations company to advise the visit.

For some notable historians this was the best opportunity to have avoided the breakdown of relations and the spiral of conflict that surrounded it. I'm not saying no. Reviewing it retrospectively is like going back over the history of what could have been, a path of lost opportunities, options, gestures that stayed there. However, it allows us to appreciate how many negative reactions, vested interests, prejudices, underestimations, arrogance, the young revolution and its top leader had already aroused in the toxic climate of the Cold War.

In fact, if you look carefully at everything that was happening in that political theater, with the benefit of time and declassified papers, the chronicle of a death foretold was already underway, the collision course between the United States and the Revolution. This was true despite the fact that that expedition was hopeful for many, including Fidel himself.

The first act of the Revolution in power had been to install the revolutionary courts, to prosecute the criminals of the dictatorship. The popularity of those processes inside contrasted with the commotion they raised outside. Instead of taking justice into their own hands, as 25 years earlier, when Machado fell, this time the trials applied the law as punishment for the repression. In January 1959, the independent Cuban press spoke of 20,000 deaths. Beyond the number of victims, the 81 months of Batistato represented a much greater cumulative effect: that of a historical hangover in which impunity had prevailed, from the time of Weyler until the last dictatorship. In the Cuba of 1959 there were living witnesses to all these pending cases. This time they were going to judge them.

Paradoxically, the first point of friction between the United States and the young Revolution had not been the agrarian reform or the nationalizations, but rather the punishment of human rights violators and its extreme transparency, which reached the point of letting in the Cuban and foreign press to the executions. Although his external image turned out to be counterproductive. Let's say, the sequence of the execution of Colonel Cornelio Rojas, police chief of Santa Clara, guilty of countless murders and torture that terrorized the city, presented an unarmed old man, dressed in civilian clothes, whose hat flew through the air under the impact of the bullets. With this bad image circulating around the world, what would not be the surprise of the Christian Science Monitor's envoys when they heard Cubans on the street who, instead of protesting the expeditious action of the courts, asked them: "Is it already Did you see how exemplary Cuban justice is?”

It is not surprising that, when those newspaper editors, fascinated with the exotic image of Fidel and the bearded men, took the initiative to see him up close, they offered him the golden opportunity, above any other economic or diplomatic interest, to convey to the people in the US, live and direct, their version of what was happening in Cuba. That was the priority. So no more asking for help or financing, he told his perplexed economists, this is going to be a visit of good will, to tell our truth. And so the delegation of 40 Cubans left, on April 15, 1959.

I am not going to review a journey that had multitudinous moments and diverse meetings, not only in the field of politics and the media, but also in civil society, with the great universities of New England—Princeton, Columbia, Harvard—and that included everything type of adventures, night walks, late-night Chinese restaurants, Latin newspapers, shaking hands with Cuban emigrants and high school students, lunches at the Foreign Correspondents' Club, visits to the Sugar Exchange and the tiger cage at the Bronx Zoo , as well as other common or unusual places, within and especially outside of plan, days typical of that first and unrepeatable time.

With his talent as a means of communication, which Cubans already knew, and his ability to charm his audiences, without reading a piece of paper and in his imperfect English, although politically very effective, Fidel also exposed himself, especially in his meetings with journalists and politicians, who subjected him to identical interrogations about the same three topics: the trials, the communist presence, the prospect of elections. This was the case, especially in the two longest and most dense sessions of his journey, with Richard Nixon and with a senior CIA officer who was an expert in the fight against communism.

Twelve years later, in his memoirs, Ambassador Bonsal refers to the objective of Nixon's meeting with Fidel in the following terms: “to underline the dangers to which the machinations of international communism could expose the naive leader of a popular revolution.”

Indeed, after two and a half hours of pedagogical talk, Nixon felt that Fidel's attitude toward the virtues of capital, elections, and the danger of communism was contradictory to that of the U.S. However, he did not believe that Fidel was a communist, but rather “incredibly naive about the communist threat.” Above all, although he was an adversary, he saw him as endowed with the qualities of a leader. “No matter what we think of him, he is going to be a big factor in the development of Cuba and quite possibly in Latin American affairs in general… we have no choice but to try to steer him in the right direction.”

This same paternalistic and visionary Nixon would change his mind regarding the Revolution and Fidel in a very short time: instead of leading them on the right path, he began to advocate the use of force to liquidate them.

The senior CIA officer repeated the same class to him, for three hours. While he smoked cigars that Fidel gave him, he explained to him the threat that the PSP posed to his leadership. The commander responded that the communists were few, and that the US exaggerated its threat in Latin America, since the little attention that the US paid to the economic and social problems of the region had a worse effect. In any case, the officer appreciated that Fidel had listened “carefully and in good faith” to his warnings, and had been willing to “continue receiving recommendations on international communism in the future.” In fact, he told the president of the National Bank that “Not only is Fidel not a communist, but he is a strong anti-communist fighter.”

The State Department's assessment of that visit was that it had been a triumph for Cuba in terms of public relations (contrary to what Bonsal thought), but that it was not going to "alter the essentially radical course of its revolution...". For them, despite having seen him speak for so many hours and with such dissimilar interlocutors, Fidel remained “an enigma.”

Nor did US policy towards Cuba change after that visit in favor of a more realistic and negotiating approach, but on the contrary. The USSR did not begin to define its policy towards Cuba until almost a year later, because the CPSU did not fully understand what was happening on the island. When a high-level Soviet delegation visited the island for the first time, in March 1960, the CIA had been carrying out its assassination plans for five months and Playa Girón had progressed from infiltration to invasion. That officer who spoke with Fidel, Gerry Droller, better known in the world of covert operations as Frank Bender, would be the head of Political Action during the attack.

I wonder what would have happened if, instead of that unorthodox strategy, Fidel had opted for the route advised by his trained economists, dedicated to managing loans, financing and seeking aid from the United States. Would they have reacted differently to an agrarian reform that maintained most of the private property in agriculture and that, however, would trigger a conflict without return with the Cuban and American sugar oligarchy, if agreements had been reached during that visit, a month earlier?

The public relations consulting company had recommended that Cubans shave their beards and wear suits and ties. Although this idea does not merit comment, in essence it is not far from the ineptitude revealed by politicians, diplomats and intelligence officers to understand the Revolution and its leadership.

As Lars Schultz has documented, they had always constructed Cubans as immature, impulsive, emotional, wild and crazy people. The Cuban upper class itself and its children reproduced this image when it came to the revolutionaries, so they continued to repeat to this day that Fidel was a madman, prone to violence and allowing himself to be provoked, and that he owed his entire ancestry to something ineffable called “the charisma".

This vision, which is not exclusive to his enemies, gives style, persuasive power, oratory and the way of projecting himself, the key to a capacity for influence that is truly sustained in political action and ideas, in the courage and the ability to defend them.

At that dawn of the Revolution, the litmus test consisted of entering “the jungle of prejudices”, that is, into the den of the wolf, with the forced foot of the other's language, and demonstrating more audacity and political intelligence than charisma. . That's the question.

Rafael Hernandez Political scientist, professor, writer. Author of books and essays about the US, Cuba, society, history, culture. He directs the magazine Temas.http://

No comments:

Post a Comment