60 years is nothing (I)

Reading a well-documented biography and the documents declassified by the three parties to the October Crisis conflict, I understood that almost nothing that we believed before had really been the case.

It was in Tad Szulc's book Fidel, a Critical Portrait , the best biography I've ever read about him, that I first read that it wasn't us, but the Soviets, who proposed installing the rockets in 1962. That view of the October Crisis was based on hours of interviews with the only living protagonist of the conflict.

The investigative journalism that Tad embodied has fewer Creole followers today, in contrast to those who want to be Oriana Fallaci or Tom Wolfe when they grow up. He would manage to record long conversations with actors of the Revolution, from both sides, some almost forgotten, like Universo Sánchez, and others as perennial as Ramiro Valdés. In the house he had rented in Marina Hemingway, where he once invited me, he told me that Fidel himself had instructed them to answer all his questions. None revealed to him, naturally, what the agreement sealed with the USSR had been.

I read the book in 1987, after the Latin America magazine of the USSR Academy of Sciences dedicated an issue to the 25th anniversary of the Caribbean Crisis —as they called it—, with a text by Sergó Mikoyan, and another by me . In chapter 5, I found out how many errors my Soviet text had , based on public sources. I consoled myself with the thought that authors considered the revealed truth about the Crisis, such as Graham Allison, Robert Divine, David Larson, Elie Abel, had made more mistakes than I had. That new view was consistent with all subsequent declassified documents and research works, especially published since the Moscow Tripartite Conference in January 1989.

Since "the one-eyed man is king," my misguided article turned me into a specialist on a subject that practically no Cuban researcher, journalist, or academic dealt with. I remember that a Party leader had given me sound advice: "Don't get involved in that subject, Rafa, because the Chief doesn't like to talk about it." What would be my surprise when, almost by accident, I ended up integrating the delegation to the international meeting of veterans and experts on the Crisis, where the third leg of the conflict, that is, Cuba, had been invited for the first time.

I am going to leave for later the intrahistory of those pioneering exchanges that led to the Havana Conference on the October Crisis, on its thirtieth anniversary, with the presence of Fidel himself. I am limiting myself here to commenting on some of the things we have learned, since the immersion in the ocean of declassified documents revealed to us the deep subpolitics, its abysses and phosphorescent creatures, as different from what is imagined from the surface. In other words, that almost nothing that we believed before had really been so.

Despite the books published later by Cuban researchers, such as Lieutenant Colonels (r) Tomás Diez and Rubén Jiménez, some commentators from the patio still refer to that moment as “when Cuba was caught in the clash between two elephants during the Cold War. » This peculiar vision of a chapter of our relations with the North only deserves to be commented on because it is repeated ad nauseam , directly or implicitly, every time our quarrels are attributed to that "bad idea" of "choosing the Russians as allies. »

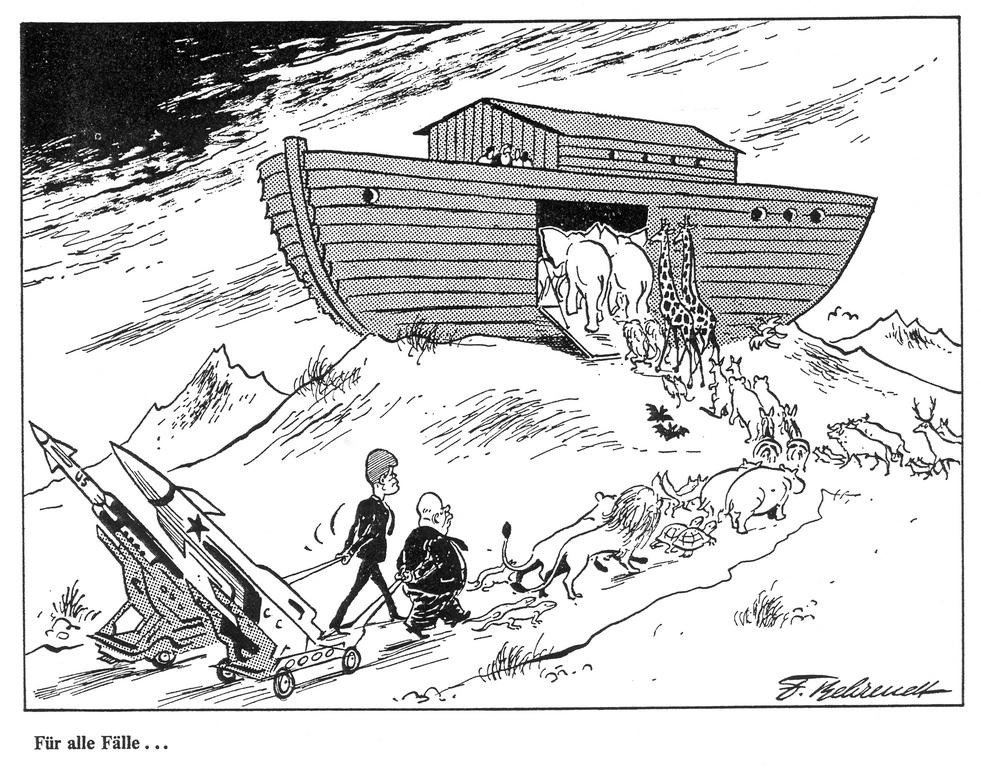

In my history classes with students from here and there, I usually illustrate the Cuban decision on the installation of the rockets through a parable. “A Little One shares the same block with a Big One. Every time he can, El Grande mouths him, shakes him, stuns him with one of those big motorcycles, to scare him and make him lower his head. One day, Chiquito is convinced that he is going to run over him with the motorcycle, and he starts looking for someone to sell him a bat. But those with bats don't want to sell it to them. Finally, he finds a Grande who lives ten blocks away, with bats of all sizes. This one, who doesn't get along with Chiquito's neighbor, offers him, instead of a bat, a machine gun. El Chiquito reasons that he does not need a machine gun, because his interest is not to shoot the neighbor, but only to appease him. He also figures out that if he says no to Grande, who has offered to support him in his fight with the dangerous neighbor, he can continue to be more and more alone than he already is in that neighborhood. In the elementary logic of aquid pro quo , or as the philosopher Adalberto Álvarez would say, of “asking for you the same as you do for me,” he decides to assume. After all, a machine gun will also appease the neighborhood handsome, even if he has an arsenal. So he agrees."

Some imagine the field of politics as a big store where you choose the shoes you like. Neither in the economy, nor in security, nor in public health, nor in meteorology does free choice function as a real premise .However, politics is judged as the territory where free will and personalities prevail. Reason of State is synonymous with malevolent and capricious vision. Speeches and slogans are confused with mirrors of profound politics. And power and its exercise end up being a kind of pathology, whose essence manifests itself in ignorance, arbitrariness, ideological blindness, or simple clumsiness of some officials there. So politics is bad by nature, according to my grandmother, who at least never presented herself as a political analyst.

Unlike other events of the past, this great event of the Cold War has the advantage that practically everything necessary to judge it has been brought to light by all three parties. So there are not only the testimonies of participants, but also the secret documents, some very revealing. I told my gringo academic friends, Argonauts on that journey, that the 15,000 declassified papers that the National Security Archives boasted about were worth the same as the handful of letters between Khrushchev and Fidel that the Cuban delegation to the tripartite meeting in Moscow had put on the table in 1990.

Not long ago, a Cuban professor, one of the first to study Russian philology, warned of confusion in the translations of those burning messages. The Russian ambassador in Havana, a KGB official who translated for the two leaders, had launched an attack where Fidel had said invasion. So the phrase "if they come to... invade Cuba, that would be the moment to eliminate such a danger forever, in an act of the most legitimate defense," was read in Moscow as "if they come to attack... Cuba, etc." Khrushchev understood that Fidel was recommending him to launch a nuclear attack against the US in case it bombed the rocket bases. «I was not unaware when I wrote them that the words contained in my letter could be misinterpreted by you and this has happened, perhaps because you did not read them carefully; maybe because of the translation, maybe because I wanted to say too much in too few lines,” the Commander replied.

In any case, the "Armageddon letter," as it has been fictionalized by some authors, arrived in Moscow after Khrushchev had already proposed a separate agreement to JFK, which bypassed Cuba. So his decision was not due to the fact that such a letter gave him the impression of emotional or impulsive. Nor because Nikita was a coward or inconsistent, as some Cuban authors have described him. But because in a fight between two Big Ones, the Little Ones don't sit down at the negotiating table. History to date would show, however, that this realpolitik or paternalistic vision entails a blundering strategic error, since without the cooperation of the Chiquitos peace cannot be achieved in most conflicts.

In any case, what Fidel was telling the Soviet Premier was that if they invaded the island, the escalation would be unstoppable. Thirty years later, in Havana, the Russian military high command in charge of the missiles revealed that there were 43,000 USSR troops here. And that although the "strategic" nuclear missiles of medium and intermediate range could not be used without Moscow's decision, some "tactical" nuclear missiles were deployed on the coasts, the discretionary use of which was up to the Soviet generals to decide in the theater of operations. .

So an invasion would have brought the forces of the two superpowers into direct combat for the first time, not just with conventional weapons, but with nuclear ones. An invasion would have been repelled with those tactical rockets, not counting Moscow, which would have triggered the dreaded Third World War.

I remember the look on the face of JFK's ex-Secretary of Defense when he found out about that "unexpected detail:" nuclear missiles that they had never photographed, as well as a bunch of warheads that had managed to reach the island before the seal was sealed. naval air blockade. At the end of the story, that letter was not wrong about the enormous danger that the US would launch the first blow, even without its highest leaders having proposed it in advance. The moral extracted by McNamara then took the form of a melancholy comment: " there's nothing like crisis management " —"there is no such thing as crisis management."

As is known, the JFK-Khrushchev pact that sealed the greatest confrontation of the Cold War did not materialize in a treaty, not even in a signed piece of paper, and left many loose ends and inconsistencies. Although Cuba did not participate in the negotiation, it was agreed that its territory should be inspected by the US and the UN. Failing that, that the US would verify the dismantling of the rocket bases through low flights over the national territory. That the Soviets remove "offensive weapons," not "medium and intermediate range rockets." So Komar missile boats, MiG 21s, and any other conventional means that could reach US territory fell within what the US could still claim.

The US commitment was limited to not invading with its troops. Nothing about paramilitary actions from US territory, support for armed groups in all provinces, terrorism and other subversive actions, provocations from the Guantánamo naval base, the total multilateral embargo.

Cuba identified with the spirit of avoiding the conflagration that had presided over the agreement, but not with the way it was negotiated, without its presence. Not only for principles of sovereignty and equity, but for having been an inalienable part of the decision to place the rockets, as well as the theater of operations. That is, for being in the front line of combat, running the greatest danger, and putting your skin first. In spite of everything, however, she cooperated with the departure of the rockets and the Soviet troops; and she was left alone with the enemy, who had never given up trying to put an end to the Revolution.

Over the next 36 months, the gentlemen who had reached the verbal agreement, JFK and Nikita, stormed out of this story. Although the agreed status quo has been respected in practice, however, as part of the ups and downs of US politics, it has been put under question marks on several occasions.

Nothing in the agreement referred, by the way, to the Soviet troops detached from the missile bases; so that more than 2,000 remained, in a unit near Havana, to "do joint exercises," as part of conventional military collaboration. Although in the channels of deep politics it was perfectly clear that, in a conflict scenario, the island would not have the Soviet umbrella, the Cuban government insisted on maintaining this group of Soviet soldiers, as a sign of the USSR's support for Cuba.

All this history has much more than what is believed to understand the present.

https://oncubanews.com/opinion/columnas/con-todas-sus-letras/60-anos-no-es-nada-i/

60 years is nothing (II)

The missile crisis, some keys to understanding Cuba’s conflict with the United States and the complex relationship with the USSR.

American Cold War literature on the Missile Crisis mimics a textbook of fantasy zoology. It was then that terms such as hawks, doves and owls were coined to characterize political tendencies, particularly in the face of major national security crises.

The hawks identified with the option of launching an immediate air strike against the island, followed by an invasion, to neutralize what was perceived as the Soviet plan to wipe out major U.S. cities with a nuclear first strike. In this cage were the former dean of the Harvard Humanities School, McGeorge Bundy, National Security Advisor to JFK; Republican businessman John McCone, director of the CIA; General Maxwell Taylor and the entire Joint Chiefs of Staff, among others. When Kennedy asked them what the Soviets would do in the face of an attack on Cuba, the head of the Air Force, Curtis Lemay, replied that “nothing, because they knew that the United States had more missiles” than they did.

The doves proposed a naval blockade of the island, with 240 warships and the closure of its airspace, a resolute military measure, but one that gave the Soviets time to reconsider and reverse the construction of bases in Cuban territory. These included former Ford Motors Chairman and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, UN Ambassador Adlai Stevenson, and JFK Speechwriter and Personal Advisor Ted Sorensen. Proposals emerged among them to negotiate with the Soviets, offering them the dismantling of U.S. missiles in Turkey, and even the Guantánamo naval base.

The owls later joined this political ornithology, who, learning from that Crisis, argued the need to avoid them through deterrent actions, because once they were unleashed, they ran the risk of being caught in a spiral of loose ends and deadly traps. Like when the first Soviet ship approached the quarantine line, and the commander of a U.S. destroyer considered firing his guns into the air, at the ship, as a “warning signal.” Or when a strategic bomber feinted in the direction of Leningrad, and the city’s radars registered it as an aborted combat mission. Or when a Soviet officer in charge of an anti-aircraft battery of surface-to-air missiles in Holguín asked the command by phone if he would shoot a U-2 that was entering his zone, he did not receive an answer, and decided to shoot it down, on October 27, later remembered as Black Saturday.

Interestingly, in those times of the Cold War, the enemies of the United States were not seen as different species of birds, but only as ferocious beasts: the Gray Bear (the USSR) or the Dragon (China). In a memorable phrase, General Lemay had argued the idea of attacking Cuba in the following way: “by wanting to put its paw in the waters of Latin America, we have caught the Russian bear in a trap, and now it had to be cut off up to its balls. Or better yet, cut off its balls at once.”

With bosses like the one in charge of the Air Force, and in the face of this haphazard escalation, JFK became so concerned that he dispatched his brother Bobby to meet with the top KGB officer in Washington, and quickly search, through a channel hidden from his top brass, for an understanding with Khrushchev, even if they had to secretly grant him the withdrawal of the U.S. missiles stationed in Turkey, as well as the public renunciation of invading Cuba and vetoing his conventional military collaboration with the island.

The same night of Black Saturday, thanks to providence and that hidden channel, Nikita would respond through the formal channel his famous proposal to withdraw the missiles, reacting to the negotiating offer received from JFK. In the next few minutes, however, another letter would arrive, signed by Khrushchev himself, in which he reaffirmed that the missiles would not be withdrawn, because they were not offensive, etc. JFK responded publicly to the first letter, and pretended the second did not exist. To put it in the animalistic language of the Crisis, instead of putting his testicles on the table, or threatening to rip them off the bear, the troubled owl made the wise decision to respond to the negotiating bear, and ignore the other.

The non-aligned countries — Vietnam, Yugoslavia, Indonesia, North Korea, Algeria, Cuba — were not identified in this political zoology, as if they were spectators who neither poked nor cut. Their images, those of screaming underage creatures, have indeed swarmed in the graphic discourse of the press, caricatures and commercial or political propaganda posters, since long before the Cold War. But no more than that.

The grey kingbird and the names of the crises

In the Moscow of 1989, where the winds of late perestroika were blowing, we Cubans, invited for the first time to the Tripartite Conference on the Crisis, had what the poet Roque Dalton had called “the turn of the offended.” In the last session of that meeting, where mainly doves attended, some already mutated into owls, as well as any number of bears, of various colors, I was the designated hitter for the Cuba team. I share here my comments from then.

Since we were there to begin to understand each other, I said that I wanted to introduce them to a Cuban bird called the pitirre (grey kingbird). Considerably smaller than all those mentioned, this bird stood out for certain qualities. He had a characteristic voice that was heard everywhere. It took it a long time to get used to being caged. And above all, it was capable of defending its territory against larger birds, regardless of the consequences. There I explained to them the meaning of the farmer phrase “it fell like a pitirre to the buzzard,” at which point I must have earned the hatred of the translators.

Finally, in the same line of analysis about the speeches, I commented on my thesis about the names of the Crisis:

In the United States it was called the Missile Crisis, because in no other event had Americans felt so exposed to nuclear weapons that they perceived as imminent danger. However, Professor Arthur Schlesinger, an adviser to Kennedy present there, had admitted to me a few years earlier, in Havana, that the psychological component of being located “in the heart of an area of vital interest prevailed over their real military threat for the United States,” that is, here in Cuba. The decision to impose naval and air quarantine had responded to this psychological factor, almost two weeks before the Pentagon had a quantified assessment of the extent to which strategic firepower had skewed in favor of the USSR. As the author of the evaluation himself, Raymond Garthoff, later revealed, the United States had continued to exceed Soviet nuclear power 15 times, even with its missiles in Cuba.

In the USSR, where it has been called the Caribbean Crisis, it was confined to the category of a regional conflict, which was not going to escalate to a global level, as the Korean War (1950-53), the Suez Crisis (1956), or later, Vietnam (1965-75). In 1989, I heard Andrei Gromyko, Soviet Foreign Minister in 1962, still claim that the brink of thermonuclear war had never really been reached. Nothing in the Pravda news resembled the alarm raised in the U.S. press in those days. So while ordinary Americans were marked forever by the prevailing panic, the Soviets continued their lives as if nothing had happened, ignorant of the seriousness of what was happening.

For their part, since 1960 Cubans had become accustomed to living with crises. That is to say, between states of alert, bombing of fields and cities, U.S. Navy warships that could be seen from the Malecón, civil war with armed groups in all the provinces, infiltrations and landings of enemy forces, militia mobilizations, maneuvers and Navy war games in the Caribbean and the Guantánamo naval base. After the Bay of Pigs, the idea of a direct U.S. invasion remained a daily notion. The 1962 October Crisis, as it was called in Cuba, only pushed that certainty to the limit. But not even its outcome closed the possibility of a conventional war, nor did it grant security to Cuba and the Cubans.

In 1965, 42,000 Marines landed in the Dominican Republic, 500 kilometers from us, and the large-scale invasion of Vietnam began. In none of these cases, nor in other Cold War military interventions, had they used nuclear weapons. But in the war of attrition against Vietnam, they did apply a scorched-earth strategy equivalent to the destructive power of several atomic bombs. In fact, the thousand conventional bombers that were ready to attack the island during the 30 days that the military mobilization lasted in 1962 could have devastated it as much or more than a nuclear attack. As is known, the contingency plan to invade us was not a paranoia of Fidel Castro, since it existed long before the Soviets appeared in Havana with the proposal of their missiles, in April 1962.

So when a historian of the stature of Arthur Schlesinger, opposed to the blockade and in favor of normalization, affirmed that “the United States never had the intention of attacking Cuba,” and mocked “the Cuban litany about CIA conspiracies,” as “a way to divert attention from the real problems of the country,” one wonders if hawks, doves and owls really learned anything from the Missile Crisis.

What is the importance of intention in politics, compared to the deliberate application of an escalation aimed at reaching the enemy’s breaking point? Or with the perpetuation of hostility? What does it mean, politically speaking, that dove presidents decided to change the regime of relations with Cuba, if the geopolitical logic and the undervaluation of the pitirres continued to foster hostility and have kept the door open for other possible crises?

It has always struck me that notable films about Vietnam such as Apocalypse Now or Platoon were dedicated to presenting the war only as an American tragedy, where the Vietnamese fighters are barely seen. Neither do Cubans appear in those dedicated to the Missile Crisis, not even when low-altitude flights could clearly portray them. It is as if they were, strictly speaking, forest birds, pitirres that barely inhabit the landscape.

Years later, I learned that the pitirre is an emblem of Puerto Rican national pride. Reclaiming this category, vilified as a gang of troublemakers, populists, hypernationalists, immature, emotional, ideological hotheads, would require learning who Ho Chi Minh, Tito, Yasser Arafat, Omar Torrijos, Gamal Abdel Nasser, Jawaharlal Nehru, Kwame Nkrumah were, and updating their legacy.

I have also wondered why the same images of the Missile Crisis are always shown on Cuban TV, with the same explanations and ideological reasoning, military narratives and discourses. Why is it that neither the press nor the schools explain the exciting vicissitudes of that drama, its problems and political lessons, nor do they show the photos taken from the RF 101 fighters flying low over San Cristóbal, nor do they explain how the hell it was suspended. Understanding that context, that of the conflict with the United States and that of our complex relations with the USSR, requires going further. To do so, you have to go back.

No comments:

Post a Comment